Britishvolt, UK car manufacturing and OE tyres

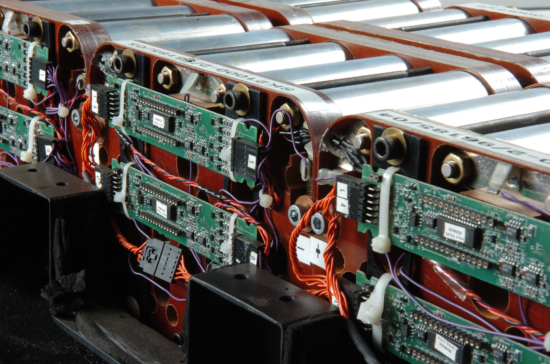

(Photo: Argonne National Laboratory; CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

(Photo: Argonne National Laboratory; CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

In May-2020, we needed a lift. We’d all been through the first and arguably harshest lockdown and Prime Minister Boris Johnson modified the COVID-19 message from “stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives” to “stay alert, control the virus, save lives”. In other words, not knowing that further lockdowns would follow, the PM was working towards easing restrictions and reopening the economy. Within the automotive sector many tyre specialists, garages and fast-fits had closed along with OEM factories and car dealerships. One result of the latter was that car production figures fell to post-war lows. What better time to back a British electric vehicle battery manufacturing gigafactory? Several projects came to the fore. There was even talk of Elon Musk considering a Tesla gigafactory in the UK. But it was BritishVolt that Boris Johnson put his name to.

With the local car industry moving towards electrification at a shocking rate, and with new car manufacturing in many cases ahead of the UK target to end the sale of new petrol and diesel petrol and diesel vehicles by 2030, the British car industry has been in a race to find the necessary electric vehicle battery capacity to support that growth. Just before the pandemic in 2019, the UK hosted the second-largest quantity of lithium-ion cell manufacturing capacity in Europe. However, with Germany, Poland and Switzerland all building their own gigafactories in the interim, domestic capacity became even more important.

Partly as a result of Johnson’s support, BritishVolt became a figurehead for that EV battery-flavoured mid-COVID fightback. The plan was for the factory to produce enough batteries for over 300,000 EVs each year, significantly supporting the UK automotive industry’s electrification and – crucially – building a foundation for “increased production of electric vehicles”.

Indeed, the government specifically said the BritishVolt project was set to create 3,000 direct highly-skilled jobs and another 5,000 indirect jobs in the wider supply chain. Just a year ago, on 21 January 2022, while still Prime Minister at that point, Boris Johnson said: “…Backed by government and private sector investment, this new battery factory will boost the production of electric vehicles in the UK…” Then business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng added: “…In this global race between countries to secure vital battery production, this government is proud to make the investment necessary to ensure UK’s retains its place as one of the best locations in the world for auto manufacturing.”

Less than a year later, on 17 January 2023, BritishVolt entered administration and appointed EY as administrator after a couple of somewhat turbulent months of seeking to necessary funding to support its ongoing existence. The same day the government’s Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee launched an inquiry into “the viability of battery manufacturing for electric vehicles in the UK”.

Committee chair Darren Jones said: “The future of car manufacturing in the UK is dependent on our ability to make electric vehicles, and to be able to export them into the EU. That means we need local supplies of electric vehicle batteries – something we’re falling significantly behind on compared to other parts of the world.”

There are a couple of rays of light for the particular BritishVolt project, with the Financial Times reporting on 31 January that: “Orral Nadjari, who founded the business in 2019 but was removed as its chief executive last summer, entered a non-binding bid for the company with administrators EY last week.”

Tyre connections

Of course, there are other gigafactory bids in the offing – not least AMTE Power’s plans to build battery cells on the site of Michelin’s former tyre factory – Dundee’s Michelin Scotland Innovation Parc (MSIP). That MegaFactory is designed to complement AMTE Power’s existing facility in Thurso, Caithness. But the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee effectively concluded that currently the Chinese-backed Envision site in Sunderland, which supplies Nissan, is Britain’s only significantly-sized battery manufacturer.

Now the committee is asking fundamental questions including: “Will the UK have sufficient battery production supplies by 2025 and 2030 respectively to meet the government phase-out plans for petrol and diesel vehicles?” And “what are the risks to the UK automotive industry of not establishing sufficient battery manufacturing capacity in the UK?”

That should make the tyre industry sit up and listen. Those questions are inextricably linked to the ever-decreasing volume of UK OE tyre demand in the UK. Without battery production, car production will continue to drop and with it OE tyre supply. Since OE tyre supply is typically the domain of premium brands, that’s a blow to large tyremakers. And if OE volumes continue to decrease, the premium brands will have to increase their UK replacement market share in order to stand still in total market terms – something that has the potential to impact the entire tyre supply chain.

With Goodyear cutting 5 per cent of its global workforce (see page 6), and with the question of whether or not Nokian Tyres is a takeover target open to discussion (see page 24), as well as the wider battery/electric vehicle narrative discussed here, this month’s features on the Car Tyre market (see page 34 onwards) as well as Motorbike tyres (see page 46 on) – both of which focus on the replacement – market, demonstrate the continuing strategic importance of the tyre trade within the wider tyre business.

This article is an example of the editorial comment that introduces every edition of Tyres & Accessories magazine. Not a subscriber? No problem, click here to become one.

Fengshen

Fengshen

Comments